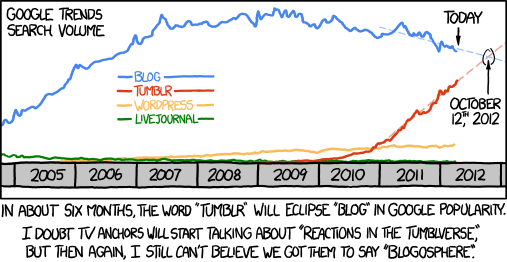

This recent xkcd comic implies that Tumblr is on its way to outpacing blogs in popularity or cultural relevance. I’m not at all sure that’s what the graph in question shows, though.

This recent xkcd comic implies that Tumblr is on its way to outpacing blogs in popularity or cultural relevance. I’m not at all sure that’s what the graph in question shows, though.

Presumably in the early days of the mass Internet you had a much higher proportion of novice users entering search terms like “Buffy website” or “game review website,” because the whole idea of a website was novel enough to seem like it needed to be included in the specification of what you were looking for—but over time people would have realized this was superfluous.

Something a bit similar has probably happened with blogs, partly out of this sort of familiarity (people realize it’s redundant to search for “Instapundit blog” or “Gawker blog” for example) but also partly because we’ve integrated blogs into the media ecosystem so fully that they’re much less of a discrete entity from, well, a website. Most major newspapers and magazines now run (or have acquired) at least one, and more often several blogs, with writers producing content on the same site in various forms. The distinctive of the form also seems less important as more traditional reported news stories are, quite incidentally, delivered in a “blog” form. So what people are now likely to think, and link, is “Writing over at Slate, Dave Weigel argues…” without splitting hairs about whether the particular item appeared as part of the Weigel blog or was classified as full-fledged Slate article.

In other words, we’ve all finally gotten it through our heads that all those panels on “blogging versus journalism” were based on a weird category error: Blogging was essentially just a particular kind of display format for writing, which could be pro or amateur, journalism or opinion, a personal essay or a corporate press release. So we understand that whether a piece of content happens to be delivered in a blog format is probably one of the least relevant things about it. That’s especially the case now that so much of our media consumption is driven by social media and aggregators—which means you’re apt to click straight through to a particular item without even noting the context in which it’s delivered, even on sites that do still maintain some kind of meaningful segregation of “articles” and “blog posts.”

As a practical matter, moreover, the ubiquity and integration of blogs means that “blog” is a much less useful search term for narrowing down your results: When everyone casually references blog posts, but actual blogs at publications are often not actually named as blogs (at The Atlantic, for instance, they’re called “Voices” and “Channels”) it’s as likely to distort your results as get you to what you’re looking for in many cases.

Tumblr, by contrast, is still ultimately one domain, and distinctive enough that if you saw something on a Tumblr, you’re apt to remember that it was a Tumblr, both from contextual clues about the site itself, and because there are still some very characteristic types of content that we associate with Tumblrs. So including “Tumblr” in your search terms is actually a really good way to quickly narrow your results so that you find that new Tumblr about MadMen/funny animated GIFs/stupid things people Tweet, as opposed to other kinds of sites which will have different types of characteristic content.

OK, so why dwell at such length on a doodle? Because there’s a general point here about how to interpret trends in online activity—whether it’s Google, Twitter references, Facebook likes, or whatever. The frequency trend over time can’t actually be interpreted straightforwardly without thinking a little bit about both broader changes in the media ecosystem you’re examining and how changing user behavior fits into the specific purposes of the technology you’re tracking. With search, the question isn’t just “are people interested in term X?” but also “is term X a useful filter for generating relevant results given the current universe of content being indexed?” You could, for instance, see a spike in searches for terms like “band” or “music”—not because people are suddenly more interested in bands or music, but because a bunch of popular bands have recently chosen annoyingly generic names like Cults, Tennis, and Girls. (For the same reason, you’d expect a lot more people to search “Girls HBO” than “The Sopranos HBO” or “Game of Thrones HBO”—just looking at the incidence of HBO would give you a misleading picture of people’s interest in HBO programming.)

In the other direction, there’s the familiar snowball effect, perhaps easiest to note in realtime on Twitter: Once a term is trending on Twitter, you can rest assured its incidence will absolutely explode, through a combination of people reacting to the fact (“Oh no, why is Dick Clark Trending? Did he die?” or “Who’s this Dick Clark guy?”) or self-consciously including it in tweets as an attention-grabbing or spamming mechanism, since users are more likely to do searches on terms they see are trending. In principle, then, you could have a set of terms with very similar frequencies in the Twitter population—until one breaks into the trending list by a tiny initial margin and then rapidly breaks away from the pack.

We’ve got such unprecedented tools for quantifying the zeitgeist in realtime that it’s become pretty common to use these sorts of metrics as a rough-and-ready estimate of public interest in various topics over time. Probably most of the time, that works out fine—but it can also give wildly misleading results if we don’t pause to think about how other factors, like context and user purposes, tend to affect the trends.

7 responses so far ↓

1 Matt Stempeck // Apr 19, 2012 at 11:50 am

Great piece. I think the case you’ve actually made is that our “great tools” aren’t that great. They measure basic metrics, but don’t tell us very much at all about what’s actually happening. Our metrics are limited by what Facebook, Twitter, etc. want us to measure, and they are nowhere standard enough to prove points or track trends across a variety of different platforms. Thanks for writing this.

2 Lindsay Lennox // Apr 19, 2012 at 3:12 pm

@Matt – I dunno, I think the tools are plenty great, but the data still requires some human eyeballs and brains to extract meaning out of it. I don’t think the two data problems Julian points to (snowballing trends and vanishing search terms) are caused by social platforms trying to control what’s measurable; I think they’re driven by folks who are still operating in a web 1.0 mindset (“pageviews = good” is another example) but being supplied with web 3.0 data they don’t know how to parse.

This is probably not a solvable problem from a data perspective – better algorithms might help extract deeper trends (and locate confounding variables like folks addending ‘band’ or ‘HBO’ to their searches), but I’m doubtful that we’ll be able to develop automated metrics that can provide a journalist with an accurate understanding of what people think about X, or a marketing person with a deep grasp of what people are saying about her product.

3 Cocktail Talk « Infinite Regress // Apr 20, 2012 at 5:51 pm

[…] Did Tumblr kill the blogosphere? […]

4 wetcasements // Apr 23, 2012 at 4:50 am

But people who use tumblr will sometimes say “I’ve got a tumblr blog” or “My blog on tumblr.”

So it’s hardly a firm distinction. Tumblr is really just stripped down blogging software with an easy to use interface and the added bonus of being very easy to incorporate links, text, and images from other people.

5 SIV // May 24, 2012 at 9:38 pm

I have a tumblr blog.

6 hamerhokie // Jun 14, 2012 at 4:51 pm

The thing that separates Tumblr from the other blogging platforms is internal linkage. Tumblr is more like a community than, say, WordPress.com. WordPress is just a collection of blogs. On Tumblr, you can follow other users, and ‘like’ other Tumblr’s articles, which creates backlinks to your Tumblr blog. So the real story is, the community nature of Tumblr is separating it from WordPress and Livejournal.

7 SocialKingMaker // May 24, 2015 at 11:04 pm

Adorable! I think you should grow more Instagram fans with SocialKingMaker.com help! Look at their website – SocialKingMaker.com