In a recent article at TCSDaily, Atheist Karl Reitz provides a prime example of what Dan Dennett calls “belief in belief.” That is, though his prose style actually seems calculated to undermine any possibility of belief in a merciful deity, Reitz wants to argue it’s a damn good thing people adhere to false religions, not on the familiar grounds that people need infinitely large postmortem sticks and carrots to behave morally, but because they will otherwise fall victim to still more pernicious “secular religions” such as fascism or communism. He writes:

A world in which everyone stopped believing in God would likely provide fertile ground for such secular faiths. These secularized religions are what we would really have if we somehow got everyone to stop believing in God. Realistically, atheists (and we atheists take pride in only thinking realistically) may only have a choice between living in societies that are traditionally religious or ones that have adopted secularized religions. [….] Even if the secular authors’ ire is well-justified, we are never going to live in a world in which the vast majority of people don’t have faith in something, whether that something is God or Government. As an atheist I feel much less threatened by someone who is willing to put off perfection by relegating it to another place than I do by someone who thinks they can create it here and now.

There’s an claim here about how dangerous, totalizing ideologies gain influence—and, implicitly, about how they have done so in the past. For the central argument here to be plausible, we need to think that the typical order of operations is that we see a mass collapse in traditional religious belief and participation, at which point destructive secular alternatives swooped in to fill the vacuum—presumably to be displaced later by either the old forms of faith or yet another “secular religion.”

There’s an claim here about how dangerous, totalizing ideologies gain influence—and, implicitly, about how they have done so in the past. For the central argument here to be plausible, we need to think that the typical order of operations is that we see a mass collapse in traditional religious belief and participation, at which point destructive secular alternatives swooped in to fill the vacuum—presumably to be displaced later by either the old forms of faith or yet another “secular religion.”

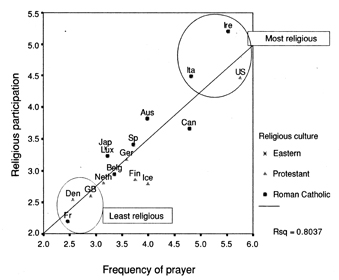

Well, as they say in Clue, that’s how it could have happened. But to the extent we can tease a pattern out of the admittedly skimpy historical data that exists, it doesn’t seem to fit very well. The 20th century did see large declines in religious participation in the developed West, but the trends don’t seem to fit this narrative, with the biggest declines coming later in the century. And while communism may have been notoriously “godless,” fascism seemed perfectly prepared to accomodate itself to traditional religion. If there’s some correlation between secularism and susceptibility to other sorts of toxic totalizing narratives, it at least doesn’t jump out of you in the graph above. What you will indeed notice is a rough correlation between secularism and an expansive welfare state, but explaining this by positing that these sorts of social-democratic governments are substitute objects of “worship” is, I hope self-evidently, just glib nonsense. It’s just as plausible to suppose, as some social scientists have argued, that the causation runs the other way: Government provision of social services removes one of the central motives for regular involvement in a church community.

To be sure, you do see upticks in religious observance in countries where a communist regime has either fallen or liberalized, but this is almost certainly a result of less active government suppression of religious practice, not a “conversion” from one faith to another. Which, I think, underscores the point of the idea of “secular religion”—a point Reitz seems to miss. It’s not (or at least, not just) a matter of atheists trying to play some cheap definitional game wherein really repugnant and murderous ideologies are simply stipulated to be “religious.” Rather, the point is that to the extent we find totalitarian ideologies that were hostile to religion, it was the totalitarianism driving the hostility rather than the irreligiousness spawning the totalitarianism. Hardcore Marxist regimes were anticlerical for the same reason religious fundamentalists are ill-disposed to other religions: They recognized competition when they saw it.

With that in mind, then, suppose we grant that in a sufficiently loose sense, it will be true that people need something to serve the “religious” function of giving meaning and direction to their lives. If we refuse to succumb to confusion about the historical cases discussed above, we’re left wondering if there’s any reason to think the secular versions are likely to be worse than the traditional alternatives. All Reitz can offer us here is the thought that secular ideologies are apt to be focused on the temporal world rather than some afterlife. Yet it’s unclear which way this is supposed to cut: It could cash out as a misguided utopianism, but it might as easily mean a perfectly healthy refusal to fatalistically accept suffering and injustice in this world, as one might if convinced all would be made right in the next. This passage, I think, shows how badly Reitz goes off the rails here:

For the same reasons that I don’t want religion taught to my [theoretical future] children in public schools, I don’t want Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth to be a requirement for graduation. If the First Amendment prohibits the teaching of religion in public schools, shouldn’t it prohibit showing that movie? After all, what’s the difference between that movie and one that presented a traditional religion in the same way?

These are the kinds of questions it is only possible to ask rhetorically. Because if you actually think about them with a view to coming up with answers, some fairly obvious distinctions present themselves. An Inconvenient Truth purports to make a series of scientific claims backed by evidence. If there’s something wrong with the film—a reason not to show it in schools—it’s that the claims are false or exaggerated by the very standards their proponents accept, and that ought to be quite enough without dragging religion into it. That some people may derive psychological satisfaction from believing certain claims in ways that shade their interpretations of the evidence isn’t really to the point.

2 responses so far ↓

1 shecky // Jun 20, 2007 at 10:08 am

After reading this post about TCS and

yesterday’s on volokh.com, I’m wondering if there’s some new meme being pushed on the right conflating religion with unproven or less than rational beliefs, no matter how secular?

2 shecky // Jun 20, 2007 at 10:31 am

This post should be:

http://volokh.com/archives/archive_2007_06_17-2007_06_23.shtml#1182281625