Opponents of war with Iraq have been arguing for some time now that, however depraved he may be, Saddam Hussein is a “rational actor,” if only in the narrow strategic sense that would make him deterrable and, by extension, make invasion unnecessary in order to contain him. I’d like to add to that the radical assumption that George W. Bush, too, is rational. Or, if that’s stretching credibility, that he’s listening to advisors who are. If that’s the case, then what, given a few more plausible assumptions about the relative preferences of the parties, can our old friend game theory tell us about the current conflict?

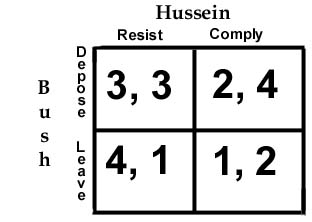

For simplicity’s sake, let’s begin with a standard two player game in a two-by-two matrix. Pretend Hussein has two fairly stark strategies to play: resist the U.N./U.S. disarmament efforts, or comply. Let’s also suppose, somewhat more realistically, that Bush has an equally stark choice between using military force to depose Hussein, and leaving him in power. We’ll represent the payoffs to each player (Bush, Hussein) ordinally, with 1 being a player’s most preferred outcome, and 4 the least favored. Hussein would most like to be left alone while maintaining his resistance, but given his palpable concern with his own well being, would probably rather give in and be disarmed than face forcible ouster. If he is attacked, though, he’d rather be able to fight back with a full array of horrible weapons — maybe try to kick off a “clash of civilizations” scenario — than go gentle into that good night. Leaving a WMD-happy Hussein in power is the outcome Bush likes least, but a costly war — lives lost and all those tasty oilfields potentially torched in the process — is only slightly more attractive. It’s a bit of a tough call between the scenarios in which Hussein is more compliant, but for the moment let’s stipulate that Bush prefers not to have to send in the Army if he’s satisifed that Hussein is playing ball. Those assumptions yield the following matrix:

In classical game theory, where both players simultaneously choose and play a strategy, this is bad news for all concerned. “Resist” is Hussein’s “dominant strategy,” which is to say, it yields a better outcome for him whatever Bush does. If Bush doesn’t depose, he’d rather Resist, and if Bush does, he’d still rather fight it out, at the least going out with a bang, or a smallpox epidemic. Bush can predict this, and his rational response is Depose, giving us Resist/Depose as the unique Nash Equilibrium. This is particularly tragic, not only because war is never much fun, but because that outcome is Pareto-dominated by Comply/Leave: both players fare better in that scenario.

Of course, the actual situation is not quite so dismal, as evidenced by the fact that we’re not actually at war yet. This is because the strategies chosen by the players are not simultaneous and independent. Bushâ??s threat is: if you donâ??t comply, then we will depose you. A sequential game of this kind is better modeled with the â??Theory of Movesâ? developed by a former professor of mine, New York Universityâ??s Steven Brams. On this model, we think of the standard matrix as a sort of game-board, with players taking turns either switching strategies or staying put, with an outcome being “final” when two consecutive turns end there. (After the first turn, that means: when someone stays put on their move, which in this instance we can think of as a player actually following through on an announced intention.)

Here, a different sort of problem arises: a problem not of convergence on a suboptimal outcome, but of failure to converge. Imagine we start in Leave/Resist, the status quo before September 11. Bush makes an opening feint, beginning to move towards Depose. On his turn, Hussein has the option of moving to Depose/Comply. He does so because, while this outcome is even worse than Depose/Resist from his perspective, he can predict that if he does so, Bush will use his turn to shift back to Leave/Comply. At that point, though, Hussein can get his best outcome by reverting to Resist, and the cycle begins anew. If this sounds familiar, it’s because this describes fairly well the cat-and-mouse game the U.S. and Iraq have been playing since the end of the first Gulf War.

(cartoon by John Bergstrom)

A cycle like this might be in Hussein’s interests. Unlike Bush, he’s not likely to be replaced by electoral “regime change” any time soon. If he can keep the game going, it seems reasonable for him to suppose that, sooner or later, the attention of the international community will turn elsewhere. Bush, however, has a piece of counterbalancing leverage. Recall that the move from Depose/Resist to Depose/Comply doesn’t immediately make Hussein better off; it is advantageous only because he can rationally expect Bush to respond by shifting to Leave/Comply. Bush may be able to forestall that play by making a credible commitment not to revert to Leave at that point, at least after a fixed set of iterations of the cycle. That explains the somewhat strident “last chance” rhetoric we’ve been hearing from Ari Fleischer with respect to Iraq’s “unsatisfactory” report. Repeatedly making public statements of that sort ties the U.S.’s threat-fullfilment credibility in future international games to its actions now, changing the payoff associated with backing off. In other words, the administration will want to attempt to convince Hussein that unless full cooperation is forthcoming now, they will invade despite future concessions or assurances from Iraq. They must, in short, appear somewhat bloodthirsty.

There is a further tangle as well. The decision to invade is fairly transparent; compliance is less so. Even with robust inspections, it is always at least possible that some further munitions or weapons labs are hidden away somewhere in Iraq. We cannot be sure whether Iraq is playing Resist or Comply. How to deal with this problem? One way would be to appear to have more information, and therefore a better idea of which strategy is being played, than we actually have. Perhaps — and this is pure speculation — this is why the administration has been so reticent about disclosing the mystery “evidence” of Iraq’s further attempts to develop WMDs. Bush may be taking a lesson from old Perry Mason shows: you can sometimes extract a confession by pretending to have more evidence than you do. This also explains why the adminstration was so quick to declare Iraq’s report — amounting, apparently, to 1,200 pages of “Oh, dude, I’m clean officer. You don’t need to check the trunk, really” — unsatisfactory. If Hussein has been holding out, he may feel compelled to disclose some of his secret programs, fearing that Bush knows about them already, and will attack unless they’re openly dismantled. Already, there have been revelations of secret arms deals with German firms in the report, something Hussein doubtless would have preferred to keep secret, since it weakens the hand of a nation opposed to war with Iraq.

Bush must walk a thin line. If Hussein believes that the U.S. is committed to invasion no matter what — eliminating the bottom half of the matrix — then Resist becomes a dominant strategy. Yet Bush must also send the message, for reasons outlined above, that he is more dedicated to invasion than would appear immediately rational. This seems like a fair description of precisely what the administration is trying to do.

One last wrinkle: are the preferences assumed for Bush correct? That is, could it be that leaving Hussein in power, even if he continues to seek WMDs, is not so bad as war from Bush’s perspective? He may appear to have the preferences assumed in the model, but that may be because only if Hussein believes that the game sketched above is the game being played might it be rational to comply. Unfortunately, even if that’s true, having made the commitment, future credibility now rests on Bush’s acting as though these are his true preferences.

What’s interesting here is that, if this analysis correctly models administration behavior, it would indicate that they do not believe, as some hawks have suggested, that Iraq is undeterrable and Hussein irrational. Instead, Bush & co. are behaving precisely as one would expect if they believed themselves to be playing against a rational opponent. Perversely, whether the administration’s strategy succeeds may now depend on Hussein’s being very different from the portrait they themselves have been painting of him.